One can liken our underappreciation of the silent clowns in the way that Mark Twain once did...

'Classic.' A book which people praise and don't read.

Last night, browsing through , I came across numerous reblogs of GQ's 50 Most Stylish Leading Men of the Past Half Century. The first one my eyes fell upon was Gene Kelly, which said:

Audiences will always imagine Gene Kelly with an umbrella and a smile; his role in Singin’ in the Rain is so iconic that it tends to overshadow everything else...

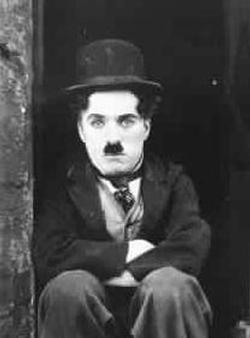

I soon became completely engrossed in the article, and was delighted to find both Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin on the list. It quickly occurred to me that, although we're all familiar with their looks and - most of all - their character costumes, there is no such immediate connection to a particular dance, gag, or scene.

I know it has all been said before. Charlie Chaplin, the ultimate silent comedian. Buster Keaton and his stone-faced acrobatics. A class apart from their cheatin', sound-usin' contemporary counterparts.

Or so you hear.

Not many people I know can admit to having seen a full Chaplin feature, and you can forget about Keaton. Don't mistake this for mocking - it took me until a month ago to intentionally watch a single frame by the Marx Brothers. How does this happen? Everybody knows the silent clowns were great, but what has your average person really watched in terms of silent comedies? There's not much one can do to remedy this through the method of blogging, but perhaps a wee taster is all you need.

Chaplin's most well-known scene is probably the table ballet. Although this is my best guess, it may only be due to Johnny Depp's re-imagining of the scene in Benny & Joon. As much as I adored this scene when I was in my young teens, it didn't send me running towards the classic film archives.

The original:

Some more elaborate scenes in his full-length films incorporate not only gags but moments that are hilarious and glow with heartfelt sincerity. This is one of my favourite sequences from The Kid, where they go about their daily routine of neighbourhood scams in order to make a living. The way he bunts the kid out of the way as they run off toward the horizon is too adorable not to giggle.

Brilliant.

One of the most iconic images of Buster Keaton depicts him with a scarf tied around his head in that old-timey way that screams, "I have toothache!" So iconic, in fact, that I cannot seem to find such a photograph; I may well have invented that one. Nevertheless, this image introduces Keaton in the short that first enamoured me to him: The Scarecrow. The one-roomed house perfectly demonstrates Keaton's incredible talent for using mechanics to create laughs. His use of objects is as multi-faceted as his comedy. Take a look.

It's difficult to condense the genius of Keaton into one short clip, since much of his comedy involved epic chase scenes and elaborate use of space and machinery. Take, for example, this short clip from Sherlock Jr. This cilp exemplifies his uncatchable, nigh-unshakable demeanour during chase sequences.

All I can do now is hope that this has whet your appetite for silent comedy. If you're interested in silent comedians and have learned all you wish to know aboutCharlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, check out some of their contemporaries: Max Linder, Fatty Arbuckle, Mack Sennett, and Harold Lloyd.

Who is your favourite silent clown?

[Images from Salon.com, NNDB, & Senses of Cinema.]